|

Synopsis:

The following synopsis has been culled from notes of the symposium sessions. It is offered here to provide some sense of the symposium’s topics and discussions, especially for those who could not attend but may wish to participate in the future. These summaries of participants’ comments are not verbatim nor are they complete, and may not be used for citation. For further information about the topics mentioned here, refer first to the participants’ published works (see the Iconic Books Bibliography) and then contact the individual participants themselves.

Thursday, October 18th:

This symposium gathered scholars working in different disciplines and specializing in different cultures and time periods to conduct collaborative research on iconic books and texts. Jim Watts (Syracuse University) introduced the symposium with a call for a comparative investigation that would avoid the dangers of over simplification, historical de-contextualization, cultural assimilation, and ideological colonization. Comparison should not aim to describe “foreign” practices but rather to provide a keener perspective on subjects and materials that we think we already know very well.

Michelle Brown (University of London, British Library) presented the evening’s keynote address, “Images to be read and words to be seen: the iconic role of the early medieval book.” Brown’s lecture charted the transformation of the Christian codex from “a cheap alternative favored by a persecuted underclass” in the early Church into sumptuous works of art in the seventh century and later. She emphasized the role of political transformations, as imperial sponsorship brought wealth and prestige to Christian book arts and later European and Insular states depended on the prestige of monastic scriptoria and their products to legitimize Christian law, teachings, and social reform. But she also emphasized the theology being worked out in the medieval illuminators art, making the Word incarnate in the divine letters representing Christ. The books produced in this way became icons, venerated, processed and enshrined just like two-dimensional portrait images of Christ and various saints. Michelle Brown (University of London, British Library) presented the evening’s keynote address, “Images to be read and words to be seen: the iconic role of the early medieval book.” Brown’s lecture charted the transformation of the Christian codex from “a cheap alternative favored by a persecuted underclass” in the early Church into sumptuous works of art in the seventh century and later. She emphasized the role of political transformations, as imperial sponsorship brought wealth and prestige to Christian book arts and later European and Insular states depended on the prestige of monastic scriptoria and their products to legitimize Christian law, teachings, and social reform. But she also emphasized the theology being worked out in the medieval illuminators art, making the Word incarnate in the divine letters representing Christ. The books produced in this way became icons, venerated, processed and enshrined just like two-dimensional portrait images of Christ and various saints.

Friday, October 19th:

The symposium proceeded on the following days with discussion sessions guided by each of the participants.

09:00: Jim Watts and Dori Parmenter (Syracuse) began by surveying their work to date on the Iconic Books Project. Watts pointed out that the Torah contains instructions for its own ritual display, performance and enshrinement in the Ark of the Covenant. Ancient Judaism built on widespread ancient practices of ritual manipulation and display of texts to elevate the Torah to unique status. , Traditional Jewish art, however, for the most part does not feature the Torah scrolls, but rather the ark that contains them. (William Scott Green had planned to attend to discuss ancient Judaism, but was forced to cancel at the last minute due to a family emergency.)

Dori Parmenter pointed out that Byzantine rituals employed icons and Gospel books for the same purposes and in the same ways. She argued that, like icons, the Christian Bible was widely believed to be an earthly equivalent to a heavenly reality. Christian illuminators and artists represented such myths in the common motif of the four evangelists being inspired by the heavenly creatures around God’s throne, and often depicted the creatures already holding the Gospels while the evangelists wrote them. Such depictions represent the Gospels, then, as heavenly books available to humans in material form.

The discussion that followed revolved around the significance of book myths in Christianity, its converse attention to human authors and scribes, and whether Christian vocabulary, like “icon,” is really appropriate for other religious traditions, such as those of India.

10:45: Vincent Wimbush (Claremont, Institute for Signifying Scriptures) presented a short documentary film, Reading Darkly, Reading Scriptures: African  Americans and the Bible, produced by ISS. It featured communities and individuals who scripturalize in a variety of ways, including liturgical dance, “holy hip hop,” a latin-Catholic home environment, the civil rights struggle, folk art, and both use and rejection of the Bible in various efforts to preserve or revive African indigenous religious practices. Wimbush used the film to describe the ongoing ethnographic research of ISS to describe scripturalizing in diverse US communities of color. He urged beginning with how people are actually interacting with their scriptures to provide as thick a description as possible of the phenomena under discussion. A significant part of that description should be the dynamic of minority cultures “waxing vernacular” with culturally dominant scriptures. Americans and the Bible, produced by ISS. It featured communities and individuals who scripturalize in a variety of ways, including liturgical dance, “holy hip hop,” a latin-Catholic home environment, the civil rights struggle, folk art, and both use and rejection of the Bible in various efforts to preserve or revive African indigenous religious practices. Wimbush used the film to describe the ongoing ethnographic research of ISS to describe scripturalizing in diverse US communities of color. He urged beginning with how people are actually interacting with their scriptures to provide as thick a description as possible of the phenomena under discussion. A significant part of that description should be the dynamic of minority cultures “waxing vernacular” with culturally dominant scriptures.

Discussion among the symposium participants focused on the film’s structure and the reactions it garners from various audiences, the multiple overtones of the phrase “reading darkly,” the power dynamics involved in scripturalizing, and the major role of performance.

2:30: Tazim Kassam (Syracuse) challenged the notion that Qur’anic calligraphy should be regarded as “iconic.” A shia tradition identifies the “speaking Qur’an” with Muhammed and the “silent Qur’an” with the book. This idea of a recited “living  Qur’an” inspires scribes to perform a devotional act by writing the text in calligraphy. The emphasis falls on writing rather than written. The context is saturated with the sounds of Qur’anic recitation, and highly elongated early scripts may be attempts to reproduce the long rhythms of recitation visually. Some of the ways that the Qur’an has been scriptured run counter to the teachings of the Qur’an itself, and aristocratic patrons have often preserved the fluidity of the Qur’an against the textualism of scholars. Qur’an” inspires scribes to perform a devotional act by writing the text in calligraphy. The emphasis falls on writing rather than written. The context is saturated with the sounds of Qur’anic recitation, and highly elongated early scripts may be attempts to reproduce the long rhythms of recitation visually. Some of the ways that the Qur’an has been scriptured run counter to the teachings of the Qur’an itself, and aristocratic patrons have often preserved the fluidity of the Qur’an against the textualism of scholars.

The discussion revolved around the normative implications of “iconic” or any other label and the difficulty in distinguishing descriptive from normative analysis of a tradition, especially given the diversity of every tradition, including Islam.

3:45: Michelle Brown (London, British Library) expanded on the her keynote address of the previous evening. She pointed out the biblical texts in which scribes and illuminators found justifications for their work: John 1:1, Jeremiah 31:33, Hebrews 10:16, Psalm 44/45:1-2. Ancient and medieval Christian authors cite a variety of biblical texts and metaphors to emphasize the place of writing and reading in Christian and monastic devotion. Writing a text like the Lindisfarne Gospels involved a great deal of physical labor and mechanical skill to manufacture the inks, paints, pens parchments, bindings and layouts for the illuminations.

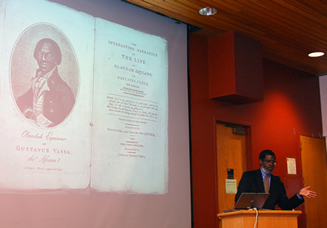

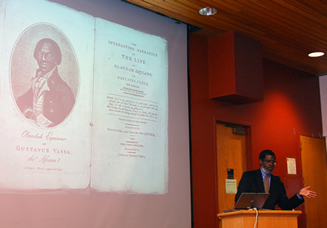

5:00: Vincent Wimbush (Claremont, Institute for Signifying Scriptures) presented the Symposium’s second keynote address, “Making Do With the Fetish: Scriptures and Vernaculars.” He focused on the case of Olaudah Equiano, who in the 18th century was enslaved in Nigeria, worked as a seaman, bought his own freedom, and eventually wrote his autobiography (published in 1789) to advance the abolitionist cause. Wimbush analyzed Equiano’s depiction of his first encounters with books and his conscious pursuit of literacy as a means to empowerment and freedom. The multiple contexts introduce interpretive ambiguities: the old, educated, relatively empowered Equiano depicted his young, enslaved, illiterate self in order to fuel commitments to the abolitionist cause. He consciously bought into the values of English society to better his own situation and then to promote political change. So many aspects of the story and alternative perspectives go unnarrated. This example illustrates the perennial one-sidedness of accounts of the encounter between oral and written cultures, between indigenous traditions and scriptural texts. It also points out how subordinate groups struggle to come to terms with the dominent cultures’ books and use them as a survival strategy. Wimbush terms such use “signifying on scriptures” and suggested that scriptures and books are not employed differently than other objects significant to the dominant culture—in Equiano’s case, paintings and clocks, for example. 5:00: Vincent Wimbush (Claremont, Institute for Signifying Scriptures) presented the Symposium’s second keynote address, “Making Do With the Fetish: Scriptures and Vernaculars.” He focused on the case of Olaudah Equiano, who in the 18th century was enslaved in Nigeria, worked as a seaman, bought his own freedom, and eventually wrote his autobiography (published in 1789) to advance the abolitionist cause. Wimbush analyzed Equiano’s depiction of his first encounters with books and his conscious pursuit of literacy as a means to empowerment and freedom. The multiple contexts introduce interpretive ambiguities: the old, educated, relatively empowered Equiano depicted his young, enslaved, illiterate self in order to fuel commitments to the abolitionist cause. He consciously bought into the values of English society to better his own situation and then to promote political change. So many aspects of the story and alternative perspectives go unnarrated. This example illustrates the perennial one-sidedness of accounts of the encounter between oral and written cultures, between indigenous traditions and scriptural texts. It also points out how subordinate groups struggle to come to terms with the dominent cultures’ books and use them as a survival strategy. Wimbush terms such use “signifying on scriptures” and suggested that scriptures and books are not employed differently than other objects significant to the dominant culture—in Equiano’s case, paintings and clocks, for example.

Saturday, October 20th:

9:00: Claudia Rapp (UCLA) emphasized the importance of cultural frameworks for interpreting the nature and function of iconic books. For Christianity in Late Antiquity and Byzantium, the visual framework was provided by debates over the honors appropriate to icons and over the nature of Christ, as well as the use of the emperor’s image to authorize courts, a practice transferred by Christian rulers to the enthroned Gospel book as the authorizing presence of Christ. The framework of writing culture provides evidence for the magical use of texts mostly on the periphery of the Roman empire. The framework of book production and scholarship increasingly centered in monasteries. The monks often opposed any private ownership of texts, criticizing them against luxury items, fearing that the object was being substituted for the message, and bemoaning the failure of lay people to read and memorize the text. The copying of scriptures was part of a monk’s initiation and devotional practice. Conversely, iconoclasts attacked many symbols of holiness, including monks themselves, and argued that hearing is better than reading because no object at all is interposed between the message and the recipient. nature of Christ, as well as the use of the emperor’s image to authorize courts, a practice transferred by Christian rulers to the enthroned Gospel book as the authorizing presence of Christ. The framework of writing culture provides evidence for the magical use of texts mostly on the periphery of the Roman empire. The framework of book production and scholarship increasingly centered in monasteries. The monks often opposed any private ownership of texts, criticizing them against luxury items, fearing that the object was being substituted for the message, and bemoaning the failure of lay people to read and memorize the text. The copying of scriptures was part of a monk’s initiation and devotional practice. Conversely, iconoclasts attacked many symbols of holiness, including monks themselves, and argued that hearing is better than reading because no object at all is interposed between the message and the recipient.

Discussion centered on the notion, found in many traditions, of the text being incarnated and transformed in the message and person of a teacher and/or disciple. Conversely, the reification of the book often occurs in reaction to historical scholarship on it. More analysis is needed of the ways in which groups describe books and icons as aides and hindrances.

10:00: Jacob Kinnard (Iliff) described the development of text veneration in Buddhism. The Theravada tradition emphasized the derivation of a text’s contents from the historical Buddha,  and the identification of such texts with the Buddha himself, i.e. the teaching in the text is the Buddha. The emergence of Mahayana led to new texts that were justified on analogy with relics of the Buddha, in fact, as better than relics. They are therefore to be displayed and venerated, as well as copied and read. Medieval Buddhist culture was very text-centered in its discourse and practices. Kinnard showed medieval reliefs that depict books set on stands being venerated by worshipers. He suggested that the Christian language of “icon” does not do justice to the Buddhist conception of these texts. and the identification of such texts with the Buddha himself, i.e. the teaching in the text is the Buddha. The emergence of Mahayana led to new texts that were justified on analogy with relics of the Buddha, in fact, as better than relics. They are therefore to be displayed and venerated, as well as copied and read. Medieval Buddhist culture was very text-centered in its discourse and practices. Kinnard showed medieval reliefs that depict books set on stands being venerated by worshipers. He suggested that the Christian language of “icon” does not do justice to the Buddhist conception of these texts.

The discussion focused mostly on the meaning of “iconic” and how appropriate it is to apply it in Buddhist and other non-Christian contexts. “Iconic” was attacked as carrying baggage that obscures a much greater fluidity of practice. The use of “iconic” was defended because it denotes an object that is both itself and a window to a transcendent reality, which is characteristic of textuality. Many participants affirmed the importance of culturally sensitive contextual interpretation and the need for a richer set of terms.

11:30: David Morgan (Valparaiso, Duke) presented a series of images of American religious  practices involving books, including Sikh rituals, Buddhist publications, Muslim calligrams, political and religious propaganda, 19th century tracts, church signs, and popular devotional art. Morgan used the images to illustrate the varied and complicated relationships between bodies, utterances and scriptures. For many in these traditions, performance matters more than script. In the case of Warner Sallman’s popular painting of Jesus, there is often conceptual slippage between the image and what it depicts. That also occurs between the text and its referent. Scholarship needs to develop ideas and vocabulary to compare how texts and images are embodied and ritualized. practices involving books, including Sikh rituals, Buddhist publications, Muslim calligrams, political and religious propaganda, 19th century tracts, church signs, and popular devotional art. Morgan used the images to illustrate the varied and complicated relationships between bodies, utterances and scriptures. For many in these traditions, performance matters more than script. In the case of Warner Sallman’s popular painting of Jesus, there is often conceptual slippage between the image and what it depicts. That also occurs between the text and its referent. Scholarship needs to develop ideas and vocabulary to compare how texts and images are embodied and ritualized.

Discussion emphasized that “iconicity” is a function of use, and that different groups and contexts (even within a single tradition) produce different ritual uses and different conceptions of the text’s function. Political change often fuels and motivates these developments, as illustrated by American Protestantism’s efforts to constrain democracy within a Christian educational context by using tracts, Bible readings, pledges of allegiance and pictures of Jesus in the schools.

2:00: Phil Arnold (Syracuse) introduced a different kind of iconic texts—papers that establish legal title to land. He described the “Doctrine of Discovery” that, in the form of several 15th and 16th century papel bulls, provided European conquerors with legal claim to the lands of the  Americas so long as the inhabitants were not Christians. Since Christian conversion had to be offered first, the invaders performed ritual readings of this Latin text, often completely out of earshot of any indigenous peoples. Mezoamerican peoples had their own paper (amatl) in which their land claims were documented. Most were destroyed by the conquistadores, which led to the production of new “native” papers (techiloyans) to defend indigenous lands. The Doctrine of Discovery continues to provide the foundation for land titles in contemporary U.S. Law and fueled popular depictions of “manifest destiny.” In Washington, D.C., civic art that depicts Indians always include books as well, visually juxtaposing subordinated natives with the land claims legitimized by texts. By contrast, in Upstate New York, Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) land claims are rooted in treaties with the U.S. Government commemorated in Wampum belts woven with purple and white shells. The belts serve to ritualize memories and are manipulated in recitals of the events, treaties and rituals that they reference. Americas so long as the inhabitants were not Christians. Since Christian conversion had to be offered first, the invaders performed ritual readings of this Latin text, often completely out of earshot of any indigenous peoples. Mezoamerican peoples had their own paper (amatl) in which their land claims were documented. Most were destroyed by the conquistadores, which led to the production of new “native” papers (techiloyans) to defend indigenous lands. The Doctrine of Discovery continues to provide the foundation for land titles in contemporary U.S. Law and fueled popular depictions of “manifest destiny.” In Washington, D.C., civic art that depicts Indians always include books as well, visually juxtaposing subordinated natives with the land claims legitimized by texts. By contrast, in Upstate New York, Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) land claims are rooted in treaties with the U.S. Government commemorated in Wampum belts woven with purple and white shells. The belts serve to ritualize memories and are manipulated in recitals of the events, treaties and rituals that they reference.

Discussion revolved around the mnemonic and ritual functions of wampum, the social institutions that preserve their meaning, and the confusion and clash of conceptual worlds reflected in stories of indigenous encounters with Western texts. Also emphasized was the arbitrary nature of Western culture’s association of law/legality with texts/papers and the considerable social, political, and economic power mediated by such texts. Comparison with indigenous cultures does not illustrate some universal features of iconic texts as much as it highlights the contingent and arbitrary nature of their roles in Western cultures.

3:15: For this session, two respondants, Brian Malley (U. of Michigan) and Deepak Sarma (Case Western Reserve), were asked to reflect on the symposium as a whole.

Malley noted the continuous debate about the validity and applicability of the phrase, “iconic book,” to the various phenomena described by presenters, but pointed out that no replacement(s) for the phrase had gathered much support. In the context of psychological and sociological theories of language, the veneration and decoration of iconic books presents a metatextual message about the text itself. But the meaning and reception of this message varies from one community and individual to another. The production and reception of iconic books often seems to involve not only power dynamics but also an element of play and of desire to participate in community. Too much emphasis on politics runs the risk of obscuring these other factors through reductionism. Malley noted the continuous debate about the validity and applicability of the phrase, “iconic book,” to the various phenomena described by presenters, but pointed out that no replacement(s) for the phrase had gathered much support. In the context of psychological and sociological theories of language, the veneration and decoration of iconic books presents a metatextual message about the text itself. But the meaning and reception of this message varies from one community and individual to another. The production and reception of iconic books often seems to involve not only power dynamics but also an element of play and of desire to participate in community. Too much emphasis on politics runs the risk of obscuring these other factors through reductionism.

Sarma aimed to provoke discussion by challenging the participants to define their terms  better. He argued that if the meaning of “iconic book” were stipulated first, the discussion of examples would be clearer and more useful. As it is, the term “icon” has skewed the focus towards Christianity. Non-Western traditions risk having only a token place in the discussion. Sarma questioned the methodological basis and goals of doing cross-cultural/religious comparison, and warned against following a model that isolates points of similarity (a la Eliade) or that searches for some common essence underlying cultural diversity (a la Hick). The discussion has sometimes seem to indicate a mystical referent that risks obscuring actual cultural phenomena. better. He argued that if the meaning of “iconic book” were stipulated first, the discussion of examples would be clearer and more useful. As it is, the term “icon” has skewed the focus towards Christianity. Non-Western traditions risk having only a token place in the discussion. Sarma questioned the methodological basis and goals of doing cross-cultural/religious comparison, and warned against following a model that isolates points of similarity (a la Eliade) or that searches for some common essence underlying cultural diversity (a la Hick). The discussion has sometimes seem to indicate a mystical referent that risks obscuring actual cultural phenomena.

The vigorous discussion that followed included these comments.

- Watts pointed out that while both Malley and Sarma focused on language, the Iconic Books Project and this Symposium were motivated by the lack of vocabulary within existing scholarship to explain the material and visual uses of texts. The juxtaposition of diverse cultural and religious uses in this symposium is intended to provoke us to think in different ways.

- Kinnard argued that the goal should not be to agree upon a common endeavor and the definition of its chief terms, but to let the contrasts show us differences. “Icon” should not be defined, but can be used to provoke these recognitions.

- Wimbush suggested that discussions like these should not be pre-defined, but rather improvized like jazz through playing around and experimenting. Considering the role of power relationships should not “reduce” the conversation but rather enrich it. Even

Christians do not agree with each other over the definition or function of icons, so the Christian origins of the vocabulary should not be thought to constrain it unduly. Christians do not agree with each other over the definition or function of icons, so the Christian origins of the vocabulary should not be thought to constrain it unduly.

- Morgan countered by observing that the word “icon” does have a fairly cohesive set of meanings tied to a specific context. Other terms, such as “talisman,” would be easier to specify and use more broadly. Studies in visual culture have recently been moving away from visual vocabulary to a more practice-centered discourse.

- Rapp noted that just collecting images in the database may itself turn them into something different because of the new context into which it places them and lead to circular thinking that turns them into icons.

4:00: Jim Watts led the final session to discuss the future of the project. He suggested that the goals for this symposium were amply achieved: it engendered a wide-ranging discussion of both cultural practices and methodological issues. How should we proceed? The most obvious path would be to carry on with several more symposia, with the goal of publishing their proceedings. But that leaves open the question of what to do with the database, if anything. Should it be published, and if so, in what form?

Participants mentioned various possible formats for the database, including a web-based database, an Icon Books wiki, the Iconic Books blog that already exists, or a print publication perhaps in encyclopedia format (which could include a CD of images).

They also discussed the methodological difficulties of doing comparison.

-

Kassam said how enriching the discussion had been, especially because it included such culturally specific examples.

-

Kinnard suggested that discussion of iconic books/texts could serve as a basis for rethinking how to do religious and cultural comparisons, since previous attempts to do comparative work have fall under heavy criticism. People inevitably make comparisons, so we should think seriously about how to do it responsibly.

-

Morgan wondered where such study fits within the taxonomy of fields of study. How will it be mediated to students?

The discussion turned to the nature of books as both material objects and texts.

-

Malley argued that to treat them as only one or the other misses the fact that the efficacy of object and of text bleed into each other.

-

Rapp suggested that the accomplishment of this symposium lay in collecting evidence that we in fact have a subject in common. The next step should examine the materiality of texts in specific kinds of settings.

Discussion then focused on who should be involved in such discussions. Particular cultures/religions should be represented by more than one voice too allow for internal disagreements to surface and prevent traditions from being essentialized. The discussion could focus on one specific kind of iconic book, e.g. image texts. A topical approach could avoid classifying participants by religion at all. But we still need to be concerned for diverse representation, and also that participants have a real interest in dealing with the topic of iconic books, however we define or specify it. Also needed are institutions to finance future meetings.

Postscript: In light of the general interest in pursuing these discussions, Jim Watts has applied to the National Endowment for the Humanities for a Collaborative Research Grant to fund two more symposia on Iconic Texts, with the intention of bringing back these participants to continue the discussions and also to expand the number and diversity of scholars involved. The goal will be to publish a collection of essays that arise out of these discussions, and create a conceptual framework within which the Iconic Books Database can be presented to a wider public.

(Thanks to Jeremy Vecchi and Sangeetha Ekambaran for taking the notes that this summary is based on, and to Daniel Cheiffer for taking the pictures!)

Jim Watts, December 19, 2007 |

![]()

nature of Christ, as well as the use of the emperor’s image to authorize courts, a practice transferred by Christian rulers to the enthroned Gospel book as the authorizing presence of Christ. The framework of writing culture provides evidence for the magical use of texts mostly on the periphery of the Roman empire. The framework of book production and scholarship increasingly centered in monasteries. The monks often opposed any private ownership of texts, criticizing them against luxury items, fearing that the object was being substituted for the message, and bemoaning the failure of lay people to read and memorize the text. The copying of scriptures was part of a monk’s initiation and devotional practice. Conversely, iconoclasts attacked many symbols of holiness, including monks themselves, and argued that hearing is better than reading because no object at all is interposed between the message and the recipient.

nature of Christ, as well as the use of the emperor’s image to authorize courts, a practice transferred by Christian rulers to the enthroned Gospel book as the authorizing presence of Christ. The framework of writing culture provides evidence for the magical use of texts mostly on the periphery of the Roman empire. The framework of book production and scholarship increasingly centered in monasteries. The monks often opposed any private ownership of texts, criticizing them against luxury items, fearing that the object was being substituted for the message, and bemoaning the failure of lay people to read and memorize the text. The copying of scriptures was part of a monk’s initiation and devotional practice. Conversely, iconoclasts attacked many symbols of holiness, including monks themselves, and argued that hearing is better than reading because no object at all is interposed between the message and the recipient.  and the identification of such texts with the Buddha himself, i.e. the teaching in the text is the Buddha. The emergence of Mahayana led to new texts that were justified on analogy with relics of the Buddha, in fact, as better than relics. They are therefore to be displayed and venerated, as well as copied and read. Medieval Buddhist culture was very text-centered in its discourse and practices. Kinnard showed medieval reliefs that depict books set on stands being venerated by worshipers. He suggested that the Christian language of “icon” does not do justice to the Buddhist conception of these texts.

and the identification of such texts with the Buddha himself, i.e. the teaching in the text is the Buddha. The emergence of Mahayana led to new texts that were justified on analogy with relics of the Buddha, in fact, as better than relics. They are therefore to be displayed and venerated, as well as copied and read. Medieval Buddhist culture was very text-centered in its discourse and practices. Kinnard showed medieval reliefs that depict books set on stands being venerated by worshipers. He suggested that the Christian language of “icon” does not do justice to the Buddhist conception of these texts. practices involving books, including Sikh rituals, Buddhist publications, Muslim calligrams, political and religious propaganda, 19th century tracts, church signs, and popular devotional art. Morgan used the images to illustrate the varied and complicated relationships between bodies, utterances and scriptures. For many in these traditions, performance matters more than script. In the case of Warner Sallman’s popular painting of Jesus, there is often conceptual slippage between the image and what it depicts. That also occurs between the text and its referent. Scholarship needs to develop ideas and vocabulary to compare how texts and images are embodied and ritualized.

practices involving books, including Sikh rituals, Buddhist publications, Muslim calligrams, political and religious propaganda, 19th century tracts, church signs, and popular devotional art. Morgan used the images to illustrate the varied and complicated relationships between bodies, utterances and scriptures. For many in these traditions, performance matters more than script. In the case of Warner Sallman’s popular painting of Jesus, there is often conceptual slippage between the image and what it depicts. That also occurs between the text and its referent. Scholarship needs to develop ideas and vocabulary to compare how texts and images are embodied and ritualized.  Americas so long as the inhabitants were not Christians. Since Christian conversion had to be offered first, the invaders performed ritual readings of this Latin text, often completely out of earshot of any indigenous peoples. Mezoamerican peoples had their own paper (amatl) in which their land claims were documented. Most were destroyed by the conquistadores, which led to the production of new “native” papers (techiloyans) to defend indigenous lands. The Doctrine of Discovery continues to provide the foundation for land titles in contemporary U.S. Law and fueled popular depictions of “manifest destiny.” In Washington, D.C., civic art that depicts Indians always include books as well, visually juxtaposing subordinated natives with the land claims legitimized by texts. By contrast, in Upstate New York, Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) land claims are rooted in treaties with the U.S. Government commemorated in Wampum belts woven with purple and white shells. The belts serve to ritualize memories and are manipulated in recitals of the events, treaties and rituals that they reference.

Americas so long as the inhabitants were not Christians. Since Christian conversion had to be offered first, the invaders performed ritual readings of this Latin text, often completely out of earshot of any indigenous peoples. Mezoamerican peoples had their own paper (amatl) in which their land claims were documented. Most were destroyed by the conquistadores, which led to the production of new “native” papers (techiloyans) to defend indigenous lands. The Doctrine of Discovery continues to provide the foundation for land titles in contemporary U.S. Law and fueled popular depictions of “manifest destiny.” In Washington, D.C., civic art that depicts Indians always include books as well, visually juxtaposing subordinated natives with the land claims legitimized by texts. By contrast, in Upstate New York, Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) land claims are rooted in treaties with the U.S. Government commemorated in Wampum belts woven with purple and white shells. The belts serve to ritualize memories and are manipulated in recitals of the events, treaties and rituals that they reference.  Malley noted the continuous debate about the validity and applicability of the phrase, “iconic book,” to the various phenomena described by presenters, but pointed out that no replacement(s) for the phrase had gathered much support. In the context of psychological and sociological theories of language, the veneration and decoration of iconic books presents a metatextual message about the text itself. But the meaning and reception of this message varies from one community and individual to another. The production and reception of iconic books often seems to involve not only power dynamics but also an element of play and of desire to participate in community. Too much emphasis on politics runs the risk of obscuring these other factors through reductionism.

Malley noted the continuous debate about the validity and applicability of the phrase, “iconic book,” to the various phenomena described by presenters, but pointed out that no replacement(s) for the phrase had gathered much support. In the context of psychological and sociological theories of language, the veneration and decoration of iconic books presents a metatextual message about the text itself. But the meaning and reception of this message varies from one community and individual to another. The production and reception of iconic books often seems to involve not only power dynamics but also an element of play and of desire to participate in community. Too much emphasis on politics runs the risk of obscuring these other factors through reductionism.  better. He argued that if the meaning of “iconic book” were stipulated first, the discussion of examples would be clearer and more useful. As it is, the term “icon” has skewed the focus towards Christianity. Non-Western traditions risk having only a token place in the discussion. Sarma questioned the methodological basis and goals of doing cross-cultural/religious comparison, and warned against following a model that isolates points of similarity (a la Eliade) or that searches for some common essence underlying cultural diversity (a la Hick). The discussion has sometimes seem to indicate a mystical referent that risks obscuring actual cultural phenomena.

better. He argued that if the meaning of “iconic book” were stipulated first, the discussion of examples would be clearer and more useful. As it is, the term “icon” has skewed the focus towards Christianity. Non-Western traditions risk having only a token place in the discussion. Sarma questioned the methodological basis and goals of doing cross-cultural/religious comparison, and warned against following a model that isolates points of similarity (a la Eliade) or that searches for some common essence underlying cultural diversity (a la Hick). The discussion has sometimes seem to indicate a mystical referent that risks obscuring actual cultural phenomena. Christians do not agree with each other over the definition or function of icons, so the Christian origins of the vocabulary should not be thought to constrain it unduly.

Christians do not agree with each other over the definition or function of icons, so the Christian origins of the vocabulary should not be thought to constrain it unduly.